Daemons work hard so you don’t have to.

Imagine that you are writing an article, Web page, or book, Your intent is to do just that – write. It’s rather nice not having to manually start printer and network services and then monitor them all day to make sure that they are working right.

We can thank daemons for that – they do that kind of work for us.

What is a Daemon in Linux?

A daemon (usually pronounced as: day-mon, but sometimes pronounced as to rhyme with diamond) is a program with a unique purpose. They are utility programs that run silently in the background to monitor and take care of certain subsystems to ensure that the operating system runs properly. A printer daemon monitors and takes care of printing services. A network daemon monitors and maintains network communications, and so on.

Having gone over the pronunciation of daemon, I’ll add that, if you want to pronounce it as demon, I won’t complain.

For those people coming to Linux from the Windows world, daemons are known as services. For Mac users, the term, services, has a different use. The Mac’s operating system is really UNIX, so it uses daemons. The term, services is used, but only to label software found under the Services menu.

Daemons perform certain actions at predefined times or in response to certain events. There are many daemons that run on a Linux system, each specifically designed to watch over its own little piece of the system, and because they are not under the direct control of a user, they are effectively invisible, but essential. Because daemons do the bulk of their work in the background, they can appear a little mysterious and so, perhaps difficult to identify them and what they actually do.

What Daemons are Running on Your Machine?

To identify a daemon, look for a process that ends with the letter d. It’s a general Linux rule that the names of daemons end this way.

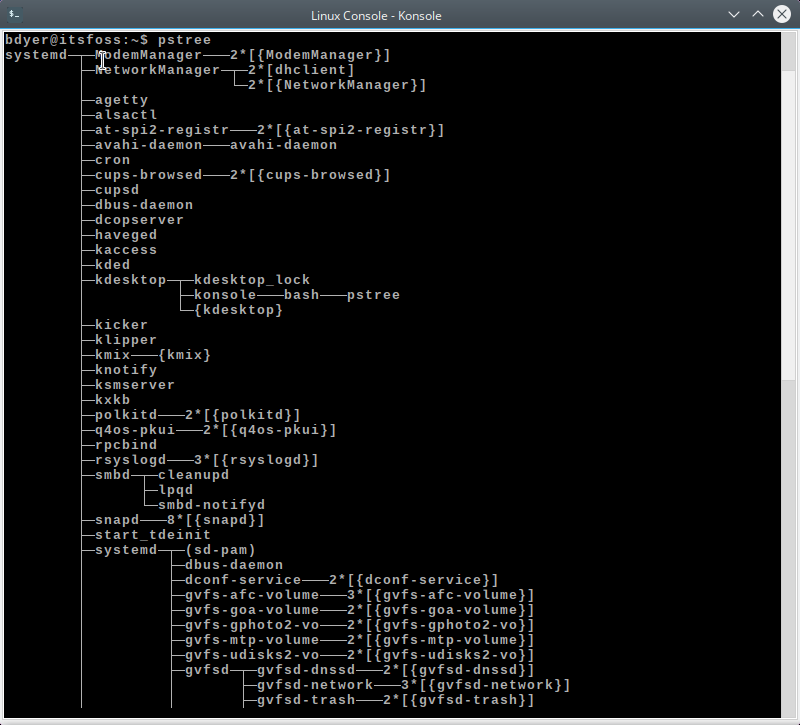

There are many ways to catch a glimpse of a running daemon. They can be seen in process listings through ps, top, or htop. These are useful programs in their own right – they have a specific purpose, but to see all of the daemons running on your machine, the pstree command will suit our discussion better.

The pstree command is a handy little utility that shows the processes currently running on your system and it show them in a tree diagram. Open up a terminal and type in this command:

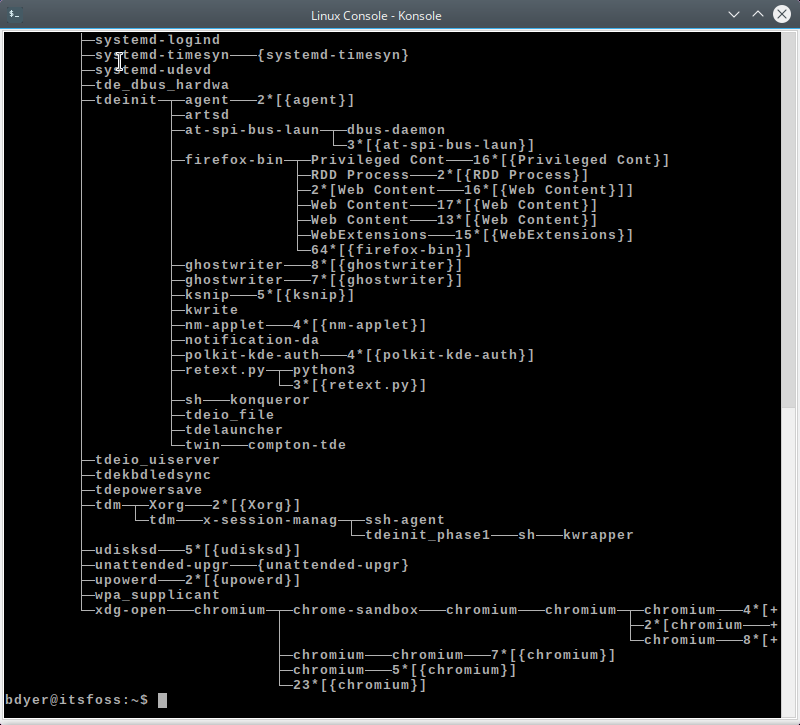

pstreeYou will see a complete listing of all of the processes that are running. You may not know what some of them are, or what they do, they are listed. The pstree output is a pretty good illustration as to what is going on with your machine. There’s a lot going on!

Looking at the screen shot, a few daemons can be seen here: udisksd, gvfsd, systemd, logind and some others.

Our process list was long enough to where the listing couldn’t fit in a single terminal window, but we can scroll up using the mouse or cursor keys:

Spawning Daemons

Again, a daemon is a process that runs in the background and is usually out of the control of the user. It is said that a daemon has no controlling terminal.

A process is a running program. At a particular instant of time, it can be either running, sleeping, or zombie (a process that completed its task, but waiting for its parent process to accept the return value).

In Linux, there are three types of processes: interactive, batch and daemon.

Interactive processes are those which are run by a user at the command line are called interactive processes.

Batch processes are processes that are not associated with the command line and are presented from a list of processes. Think of these as “groups of tasks”. These are best at times when the system usage is low. System backups, for example, are usually run at night since the daytime workers aren’t using the system. When I was a full-time system administrator, I often ran disk usage inventories, system behavior analysis scripts, and so on, at night.

Interactive processes and batch jobs are not daemons even though they can be run in the background and can do some monitoring work. They key is that these two types of processes involve human input through some sort of terminal control. Daemons do not need a person to start them up.

We know that a daemon is a computer program that runs as a background process, rather than being under the direct control of an interactive user. When the system boot is complete, the system initialization process starts spawning (creating) daemons through a method called forking, eliminating the need for a terminal (this is what is meant by no controlling terminal).

I will not go into the full details of process forking, but hopefully, I can be just brief enough to show a little background information to describe what is done. While there are other methods to create processes, traditionally, in Linux, the way to create a process is through making a copy of an existing process in order to create a child process. An exec system call to start another program in then performed.

The term, fork isn’t arbitrary, by the way. It gets its name from the C programming language. One of the libraries that C uses, is called the standard library, containing methods to perform operating services. One of these methods, called fork, is dedicated to creating new processes. The process that initiates a fork is considered to be the parent process of the newly created child process.

The process that creates daemons is the initialization (called init) process by forking its own process to create new ones. Done this way, the init process is the outright parent process.

There is another way to spawn a daemon and that is for another process to fork a child process and then die (a term often used in place of exit). When the parent dies, the child process becomes an orphan. When a child process is orphaned, it is adopted by the init process.

If you overhear discussions, or read online material, about daemons having “a parent process ID of 1,” this is why. Some daemons aren’t spawned at boot time, but are created later by another process which died, and init adopted it.

It is important that you do not confuse this with a zombie. Remember, a zombie is a child process that has finished its task and is waiting on the parent to accept the exit status.

Examples of Linux Daemons

Again, the most common way to identify a Linux daemon is to look for a service that ends with the letter d. Here are some examples of daemons that may be running on your system. You will be able to see that daemons are created to perform a specific set of tasks:

systemd – the main purpose of this daemon is to unify service configuration and behavior across Linux distributions.

rsyslogd – used to log system messages. This is a newer version of syslogd having several additional features. It supports logging on local systems as well as on remote systems.

udisksd – handles operations such as querying, mounting, unmounting, formatting, or detaching storage devices such as hard disks or USB thumb drives

logind – a tiny daemon that manages user logins and seats in various ways

httpd – the HTTP service manager. This is normally run with Web server software such as Apache.

sshd – Daemon responsible for managing the SSH service. This is used on virtually any server that accepts SSH connections.

ftpd – manages the FTP service – FTP or File Transfer Protocol is a commonly-used protocol for transferring files between computers; one act as a client, the other act as a server.

crond – the scheduler daemon for time-based actions such as software updates or system checks.

What is the origin of the word, daemon?

When I first started writing this article, I planned to only cover what a daemon is and leave it at that. I worked with UNIX before Linux appeared. Back then, I thought of a daemon as it was: a background process that performed system tasks. I really didn’t care how it got its name. With additional talk of other things, like zombies and orphans, I just figured that the creators of the operating system had a warped sense of humor (a lot like my own).

I always perform some research on every piece that I write and I was surprised to learn that apparently, a lot of other people did want to know how the word came to be and why.

The word has certainly generated a bit of curiosity and, after reading through several lively exchanges, I admit that I got curious too. Perform a search on the word’s meaning or etymology (the origin of words) and you’ll find several answers.

In the interest of contributing to the discussion, here’s my take on it.

The earliest form of the word, daemon, was spelled as daimon, a form of guardian angel – attendant spirits that helped form the character of people they assisted. Socrates claimed to have one that served him in a limited way, but correctly. Socrates’ daimon only told him when to keep his mouth shut. Socrates described his daimon during his trial in 399 BC, so the belief in daimons has been around for quite some time. Sometimes, the spelling of daimon is shown as daemon. Daimon and daemon, here, mean the same thing.

While a daemon is an attendant, a demon is an evil character from the Bible. The differences in spelling is intentional and was apparently decided upon in the 16th century. Daemons are the good guys, and demons are the bad ones.

The use of the word, daemon, in computing came about in 1963. Project MAC is shorthand for Project on Mathematics and Computation, and was created at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. It was here that the word, daemon, came into common use to mean any system process that monitors other tasks and performs predetermined actions depending on their behavior, The word, daemon was named for Maxwell’s daemon.

Maxwell’s daemon is the result of a thought experiment. In 1871, James Clerk Maxwell imagined an intelligent and resourceful being that was able to observe and direct the travel of individual molecules in a specific direction. The purpose of the thought exercise was to show the possibility of contradicting the second law of thermodynamics.

I did see some comments that the word, daemon, was an acronym for Disk And Executive MONitor. The original users of the word, daemon, never used it for that purpose, so the acronym idea, I believe, is incorrect.

Lastly – to end this on a light note – there is the BSD mascot: a daemon that has the appearance of a demon. The BSD daemon was named after the software daemons, but gets is appearance from playing around with the word.

The daemon’s name is Beastie. I haven’t researched this fully (yet), but I did find one comment that states that Beastie comes from slurring the letters, BSD. Try it; I did. Say the letters as fast as you can and out comes a sound very much like beastie.

Beastie is often seen with a trident which is symbolic of a daemon’s forking of processes.